Lessons in procurement and contract management

Introduction

This report brings together what we have learned in recent years about tertiary education institutions’1 (TEIs) procurement and contract management processes.

Its purpose is to help TEIs and other public organisations understand “what good looks like” so they can identify and focus on areas that will best improve their practice.

Its purpose is to help TEIs and other public organisations understand “what good looks like” so they can identify and focus on areas that will best improve their practice.

Spending on supplies and services is fundamental to TEIs’ ability to provide educational services. For example, Te Pūkenga’s 17 subsidiaries comprise of 16 former institutes of technology and polytechnics (ITPs), and Work Based Learning Limited. They spent approximately $350 million on purchasing supplies and services from external organisations in 2021, representing a third of total expenditure.2 TEIs use a range of procurement and contract management approaches. This is to be expected. Contracts for the diverse array of goods and services that TEIs rely on may best be procured in different ways. However, there is scope for improvement. Some practice is below the standard we consider to be appropriate for the scale and importance of external sourcing in the sector.

Against a backdrop of ongoing vocational education reforms, the Covid-19 pandemic, rising inflation, and supply chain disruption, it is important that the sector understands and implements good procurement practices. Carefully managing the processes used for purchasing and contract management can reduce some of the risks associated with challenging operating environments. Well-designed and well-implemented procurement processes maintain market trust and confidence, generate competition, and help demonstrate that best public value is being achieved. Robust contract management helps ensure that the value achieved through procurement is delivered in practice

Vocational education reforms

The creation of Te Pūkenga’s creates both challenges and opportunities. The new organisation will have to decide which aspects of procurement and contract management to consolidate and which to devolve.

Te Pūkenga has the potential to embrace good practice in procurement and contract management, leverage its enhanced buying power, and support subsidiary companies to make improvements that benefit local suppliers. However, there are risks that procurement practices may become less efficient, existing knowledge of tertiary sector procurement may be lost, and residual functions left with existing polytechnics may be inconsistent, poorly resourced, or inadequately co-ordinated.

The Government Procurement Rules and policies expect public organisations to:

- meet the five Principles of Government Procurement;

- deliver public value by getting the best possible result from procurement, including looking for opportunities to deliver broader economic, social, environmental, and cultural benefits from spending public money; and

- meet the expectations of the Government Procurement Charter for how organisations should conduct their procurement activity to achieve public value.

The creation of Te Pūkenga marks a step change in the purchasing power to support vocational learning in New Zealand. How that power is used will be a significant factor in the new organisation’s success.

How Te Pūkenga addresses these challenges will provide lessons for other reforms across the public sector.

We found that Te Pūkenga recognises these risks and opportunities. The former ITPs will be fully integrated with Te Pūkenga by November 2022. From then, Te Pūkenga will have the mandate to establish governance over procurement and contract management. Te Pūkenga plans to review the current procurement policy in November 2022, with the support of the former ITPs. Alongside this, the operating model for a national procurement function will be designed and implemented. If the procurement policy has not been approved by November 2022, the former ITPs will continue to use their own policies under a ‘grandfather clause’. The review will provide the opportunity to ensure there are consistent and effective processes operating across the country. In the meantime, ITPs continuing to apply their existing policies, procedures, and procurement approaches is helping to ensure continuity through transition.

We hope that this report has lessons for organisations going through change and consolidation, as well as for organisations operating in a challenging environment.

Questions to ask when spending public money

This report presents ten critical questions that TEIs, Te Pūkenga, and all those spending public money need to ask themselves. The answers will help to determine whether procurement processes are well-managed, deliver the desired outcomes, and achieve value for money.

Strategic approach

- Does the organisation have a clear view of its longer-term procurement needs?

- Does the organisation take a strategic approach to contract management (for example, focusing effort on critical supplies)?

Policies and procedures

- Are policies and procedures up to date?

- Do they provide practical guidance for decision-making?

Staff experience and capabilities

- Does the organisation have sufficient experienced and capable procurement staff?

- Is training and guidance available to staff so that they can put policy into practice effectively?

Structured planning and market analysis

- Do procurement managers understand the supply markets that they engage with and the key factors affecting supplies of goods and services?

Effective contract management

- Does the organisation give adequate attention to contract management processes, including contract completion and transition?

Information management

- Are appropriate information management systems in place to collect and report data on spending activity in a way that helps inform future decisions?

Review and improvement

- Is the performance of procurement and contract management regularly reviewed, and do reviews lead to meaningful change?

The fundamentals of procurement

Procurement is the overarching term used to describe the business of purchasing.

Procurement is much more than “buying something” – it includes all the processes involved in acquiring goods and services from a third party, from initiating a project and identifying a need through to sourcing a supplier and managing the relationship with that supplier. Procurement is often used to describe just the planning and sourcing stages. Effective contract management completes the cycle and helps ensure goods and services are delivered well, to specification, and in full. Together, effective procurement and contract management can help to ensure that public value is realised.

Like many public organisations, TEIs are highly reliant on the private and not-for-profit sectors, which provides particular challenges to TEIs when ensuring good financial control. Capital investment, together with procuring and managing contractors, is crucial to improving assets and enabling TEIs to operate smoothly. Well-maintained assets, services, and facilities further contribute to revenue by attracting students.

Procurement and contract management carry high risks to cost control, public reputation, and performance, impacting future financial viability. Getting procurement and contract management right reduces these risks as well as achieving value for money. As New Zealand and the TEI sector continues to experience a period of economic uncertainty, it is important that procurement and contract management controls remain strong.

We expect up to date policy, procedures, and guidance, which comply with good practice and the Government Procurement Rules, to set a firm platform for controlling procurement. Organisations should review their procurement and contract management practice and use this experience to support improvement.

Figure 2 – The eight-stage life cycle of procurement

Source: (Recoloured from) the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment.

Changes ahead

Leadership and central coordination are needed to deliver change and a fully effective procurement function.

The Office of the Auditor-General’s report Using ‘functional leadership’ to improve government procurement (November 2019) emphasised the benefits of central co-ordination and leadership to an effective procurement function.

Strong leadership will be required to deliver the change signalled in the 2019 edition of the Government Procurement Rules. The updated Rules state that the strategic goal for government procurement is to achieve public value. The Government Procurement Charter is included in the Rules. It sets out national priorities for improving and delivering public value. New and innovative approaches are likely to be required. Meanwhile, Te Kupenga Hao Pāuaua, the Government’s progressive procurement kaupapa, aims to increase the diversity of government suppliers, starting with Māori businesses. A firm basis in policy, accompanied by transparency and accountability, are key to maintaining the trust and confidence the market needs in order to see TEIs as valuable customers.

TEIs need to respond proactively to current challenges to uphold good procurement practices in a time of change. The Auditor-General defines good procurement through the principles of accountability, openness, value for money, lawfulness, fairness, and integrity. The Government Procurement Rules determine the need to:

- plan and manage for great results;

- be fair to all suppliers;

- get the right supplier;

- get the best deal for everyone; and

- play by the rules.

These principles help to achieve value for money as well as achieving broader outcomes. Applying these principles in practice helps achieve value for money and broader outcomes. Good contract management ensures this value is then delivered in practice. Improving contract management reduces risk by improving the control, monitoring and administration of contracts.

Impacts of uncertainty

For the most part, TEIs have dealt positively with the widespread effects of the Covid-19 pandemic on procurement and contract management. When asked, most described these effects as ‘manageable’.

Most TEIs have had to contend with challenges in sourcing certain goods. Supply chain delays and other issues combined with price escalation were also cited as challenges. However, TEIs have managed to deal with these challenges and have found ways of communicating effectively with suppliers and resolving invoicing and payment issues.

The former ITPs that make up Te Pūkenga’s have continued to purchase supplies and services from external organisations as usual during a period of significant uncertainty.

The creation of Te Pūkenga’s provides an opportunity for the sector to build on existing good practice and address the issues we have raised in this report. Te Pūkenga’s has the potential to provide clear leadership and share learning across its subsidiaries. It will have a stronger base from which to exert influence in supply markets.

Our approach

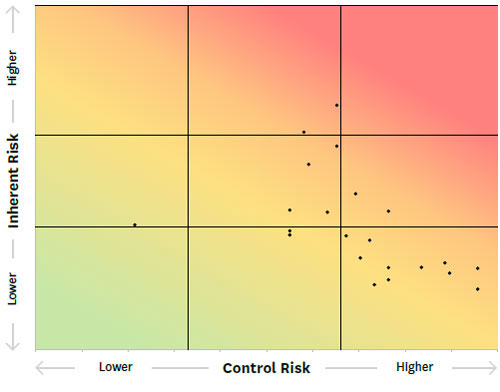

In 2020, we completed an initial assessment of the risks to good procurement and contract management faced by the 22 TEIs that are audited by Audit New Zealand. This gave us a good overview of the challenges faced by the sector.

We considered aspects of procurement and contract management at each of the organisations, based on our cumulative audit knowledge and experience of each organisation. In addition to understanding their approach, our work enabled us to better understand the challenges that they face.

We used recognised good practice and our sector expertise to develop a standardised risk assessment tool to analyse each organisation’s approach to procurement and contract management. These risk assessments allowed us to identify areas of relative strength and weakness and suggest improvements.

In 2022, we followed up our 2020 risk assessments through a survey of TEI procurement and contract specialists, which received a 72% response rate. The survey results allowed us to build on our understanding and confirmed our assessment of procurement and contract management across the sector.

Our risk assessment tool

Our assessment tool considered two aspects of risk:

Inherent risk – This is risk that arises from the factors that impact an organisation: complexity, instability, change, delivery of critical services, interdependencies, and reliance on third parties. Size, strategic direction, skills, and capacity are also important.

Control risk – This is risk that may arise from poor management of the systems and processes put in place to mitigate inherent risk. Our assessment of controls was based on their design, not their operation, and covers the main aspects of good practice that we would expect an organisation to apply.

Inherent risk was classified on a scale from low to high, and the design effectiveness of controls was classified on a four-point scale from basic to advanced. We awarded a risk score to each classification. A description of the control classifications is shown in the table below.

| Control Classification | Control Description |

|---|---|

| Advanced | There is a strong level of internal control. The organisation is an exemplar of good practice. |

| Intermediate | Most good practice is in place. Internal control is good. This is an effective level of control for mid-sized organisations such as TEIs to aim for. |

| Core | Essential management arrangements are in place. Internal control is generally adequate. |

| Basic | A basic approach, appropriate for the smallest organisations. For complex organisations such as TEIs, internal control is likely insufficient. |

Our assessment of the TEI sector

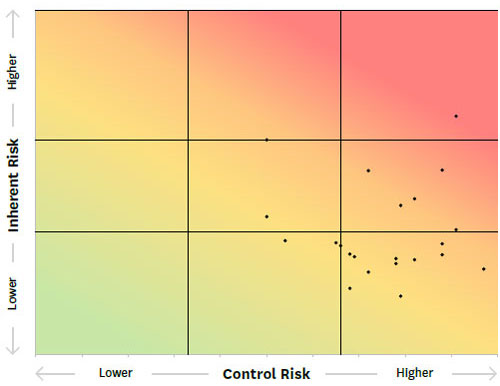

Our risk assessments found that contract management is generally weaker than procurement, particularly in larger, higherspending TEIs.

We also found that there have been minimal changes to the way TEIs approach and manage procurement and contract management since 2020. Levels of residual procurement risk are higher than we would expect.

The management arrangements for procurement and contract management are important, but there is no right or wrong approach. The most appropriate structure is a matter for consideration and decision at each organisation. A small number of TEIs have an entirely devolved structure to manage their procurement function, but the majority have centralised arrangements for large procurements, with delegated authority for lowervalue procurements.

Our work found little evidence of advanced practice in the sector. Most organisations self-assess their arrangements as being at a core or intermediate level, although a quarter of those surveyed consider their arrangements to be at an advanced level. Despite the positive self-assessment by a quarter of organisations, evidence of good practice within the sector is limited and we consider that the sector has substantial ground to make up in relation to both procurement and contract management before it can maximise the benefits from its relationships with suppliers. Our analysis found some organisations are operating at a basic level in a wide range of areas, undertaking procurement and contract management activities below what we consider to be an appropriate standard for the size and complexity of a TEI.

Many smaller organisations have scope for improvement in both areas. Although they have lower inherent risk than some other parts of the public sector, they exhibit high control risk due to their lack of maturity in both procurement and contract management.

Levels of inherent risk vary widely depending on such factors as the size, location, and nature of the organisation, as well as the extent of their approach to outsourcing and the maturity of the local market. There is little a TEI can do to reduce its level of inherent risk. Our analysis shows inherent risk in TEIs to be generally at a low to medium level for procurement and contract management compared to larger public organisations. This means that TEIs do not necessarily need to invest in expensive or complex systems to help them manage procurement more effectively. Some simple improvements are likely to be just as effective and more appropriate to the scale of the task.

Smaller TEIs are more likely to have higher levels of control risk. This may be a consequence of their staff capacity and overall resource availability. The job market in New Zealand has been impacted generally by Covid-19 and we recognise it will take some time for resourcing challenges to be addressed across the public sector. Accepting higher control risk can be a reasonable position to take if the inherent risk being managed is low. However, we found that some large organisations have high levels of control risk. In some cases, this risk was beyond that which would be expected given their profile and reputation in the sector.

In the charts below, each dot represents a TEI mapped according to our assessment of its inherent risk and its control risk.3 With very few exceptions, the chart shows a need for TEIs to move towards the green areas by reducing control risk. We expect organisations with higher inherent risk to have correspondingly stronger controls.

The charts show:

- a cluster of smaller organisations with high control risk;

- some organisations with a high level of both inherent and control risk; and

- too many organisations in the red and amber risk ratings.

Procurement Risk Assessment

Contract Management Risk Assessment

Common areas of risk across TEIs

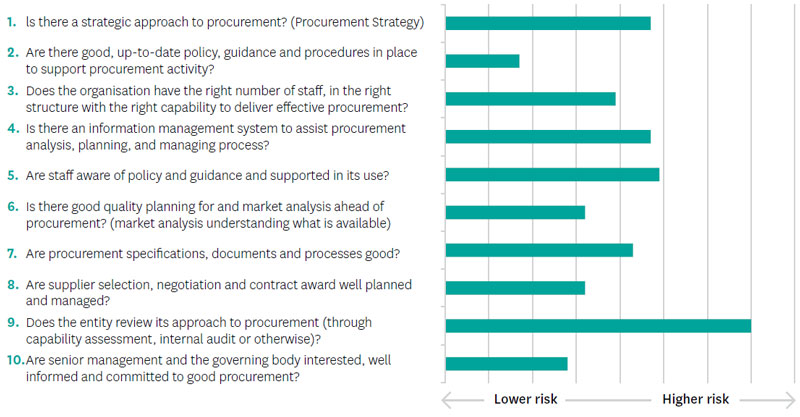

We structured our assessment of controls against 10 areas of contract management activity and 10 areas of procurement practice.

The graphs below show the aggregated risk rating we assessed for the 22 TEIs audited by Audit New Zealand and illustrate areas of control that we judged to be stronger or weaker. A higher aggregated score indicates a higher risk and weaker control. The graphs also indicate that lack of sophistication in contract management controls presents higher levels of risk than those covering the purchasing stage of the procurement cycle.

Procurement Controls

Contract Management Controls

Our conclusions are listed below, in areas where we see most scope to strengthen procurement and contract management.

1. Strategic approach

What does good look like?

We expect evidence of long-term planning, with an annual procurement plan or strategy in place, and senior management approval and oversight.

We expect a strategic approach to contract management, informed by categorisation that differentiates between the relative importance of suppliers (for example, strategic partners, routine suppliers, and commodities).

We expect contract management plans to be applied to significant contracts, with risks to contractor delivery identified and managed.

Highlights for improvement

|

We found that most TEIs are not taking a strategic view of procurement and contract management. Some TEIs do not have a procurement strategy or a document which might serve the same purpose. This can result in a repetition of existing practice regardless of changing circumstances.

Our assessment showed that only four TEIs have procurement arrangements in place that exceed our expectations for an appropriate strategic approach. Four further TEIs have arrangements which do not meet the expected requirements. Our work indicates that many TEIs are responding to procurement needs as they arise rather than taking a longer-term view.

Our work exposed a similar situation in relation to managing supplier relationships. Only one of the organisations we reviewed had arrangements that we considered to be better than the minimum appropriate standard, with over a third of the organisations reviewed having an approach which was below that standard.

We accept that staff capacity and poor information systems can constrain an organisation’s ability to think strategically, but our findings suggest that in most TEIs procurement and contract management activities are not given the profile, priority, or attention they deserve. They are typically too responsive to immediate needs, with insufficient regard for longer term objectives.

Structured planning can support contract management and improve decision-making by identifying and managing risk. Plans for better contract management may include supplier categorisation (differentiating between the relative importance of suppliers, for example, strategic partners, routine suppliers, and occasional needs). Better specification of contracts are also useful. Well-drafted contracts can enable stronger performance monitoring of those contracts which in turn increases the opportunity to identify areas for improvement.

2. Policy, procedures, and guidance

What does good look like?

We expect there to be an organisation-wide policy or consistent suite of policies in place that apply across all procurement activity (such as opex, capex, and grants) and all contracts (such as commercial, capital works, and strategic partnerships). These should be up to date and supported by detailed guidance, procedures, templates, and standard contracts.

We expect guidance on what to do when contract performance obligations and expectations are not being met, so that suppliers are treated fairly and the organisation gets the full value it has procured. The approach to negotiating and approving contract variations should be clear with reference to delegated authority.

Highlights for improvement

|

We found TEI policy and procedures to be an area that is addressed relatively well in procurement but less so in contract management. Although sometimes policies are incomplete or out of date, some 40% of TEIs have policies, procedures, and guidance for procurement that exceed the core requirements. However, policy is the place to signal intent, and making clear policy statements on the strategic nature of procurement may help it to become more proactive rather than process-led. In contract management, 20% of TEIs have policies, procedures, and guidance that exceed the core requirements, although some organisations have up-to-date policies and procedures that we recognise as supporting their procurement activity. One university has developed a contract management framework together with supporting policy and guidance templates. Such frameworks provide clarity for staff and aid consistency of approach.

Policy, procedures, and guidance should be regularly reviewed and updated to ensure they remain consistent with good practice and current Government Procurement Rules. A consistent approach should be documented for all types of procurement activity (for example, operating, capital, and grants), starting at policy level and supported by detailed guidance, procedures, and templates. Other areas of policy and guidance which should be considered include ethical issues such as conflicts of interest, gifts and hospitality, managing contact with providers, and confidentiality. Guidance on what to do when contract performance obligations and expectations are not being met is also beneficial.

As Te Pūkenga’s develops its role and approach to procurement, our work indicates two policy areas to focus on:

- defining its own policy position, for centreled procurement and well as defining which procurement and contracting is centralised and which is devolved; and

- in structures like Te Pūkenga’s, which bring together multiple organisations, policy needs to be coherent and consistent.

3. Staff capacity and capability

What does good look like?

We expect procurement and contract management to be led by a Centre of Excellence, a dedicated team, or a Chief Procurement Officer so that leadership and accountability is clear. The Centre of Excellence can provide advice and guidance. We expect good oversight and co-ordination of staff with devolved procurement responsibility, with role numbers reflecting the need to effectively deliver the service.

We expect training and development to be available to staff so that policy is put into practice as intended.

Highlights for improvement

|

We found that staffing levels are deemed by most organisations to match their requirements. However, many organisations rely on a small number of staff, and in some cases responsibility for procurement is allocated to staff who have other demanding functions. This increases risk related to business continuity and may place staff under pressure. Developing the competency of staff to discharge their responsibilities is a duty of management but we recognise how challenging this can be, particularly for small organisations and those located in areas where the pool of specialist knowledge is limited. Nevertheless, we acknowledge the training that takes place to equip staff to deliver their roles and we encourage qualifications and training to support wider professional development. Structured training to supplement experience with qualifications is preferred.

We found there to be slightly greater capacity and capability in procurement than for contract management. Our work showed staffing capacity and capability to be at a basic level for contract management in about a third of TEIs. Of these, many were also operating at the same level for procurement, meaning that we found a strong correlation between organisations whose procurement was weak and those whose contract management was also weak. We assessed only 14% and 23% of organisations as operating above the expected standard for both contract management and procurement respectively. All such organisations are in urban areas. Smaller TEIs could source external specialist expertise to supplement existing skills.

Role numbers should reflect the need to deliver the functions effectively. Our review indicates that effectiveness is helped where it is possible for procurement and contract management to be the principal responsibility of a dedicated team under the supervision and guidance of a Chief Officer or similar post.

The University of Canterbury has a range of dedicated staff in procurement roles, while contract management operates on a decentralised basis and is often combined with other functional responsibilities. The university has demonstrated its commitment to alternative options by reviewing responsibilities for contract management within the decentralised structure. This is one example of a TEI thinking creatively to ensure it has the right level of expertise dedicated to procurement and contract management.

4. Quality of planning and market analysis

What does good look like?

We expect significant procurements to have appropriately skilled teams, budgets in place ahead of procurement, financial delegations to be clear, and approvals obtained prior to procurement.

We expect business cases to justify significant procurements, with formal procurement that assesses procurement risks.

We expect a good understanding of the market and operating environment and a clear rationale for adopting procurement approaches.

Highlights for improvement

|

We considered supplier selection, negotiation, and contract award to be managed well in 32% of organisations, although there remains scope to improve procurement specifications and other documentation. We assessed the practice of TEIs to be below minimum requirements in 18% of the organisations we reviewed. In some locations we were told that there is a very limited market for certain goods and services and that this reduced TEI’s ability to gain advantage from market analysis.

Structured planning and market analysis enables procurement managers to understand how the supply market works and the key suppliers for goods and services. Good market analysis can help determine the best approach, helping buyers to achieve better value for money through reduced prices or improved service. This can be achieved through better identification of relevant stakeholders, good use of appropriately skilled teams for significant procurements (for example, producing clear business cases to justify the rationale for significant procurements), and linking risk analysis and management to strategic objectives.

5. Contract management and delivery practice

What does good look like?

We expect contract managers to be identified for all contracts.

We expect a good approach to setting out requirements and defining quality in contracts. We expect regular reporting, monitoring, and evaluation of delivery.

We expect effective working relationships with supplier and key stakeholders, with good feedback provided to contractors on their performance.

Highlights for improvement

|

Although our assessment found that 65% of organisations have arrangements in place that exceed basic requirements, we found little evidence of dedicated contract managers, even in larger organisations. Contract management is a role which is often allocated to staff alongside other duties, resulting in some areas of contract management not receiving the attention they require.

In addition to monitoring providers’ performance, time should be made for maintaining relationships with suppliers, including giving feedback. At an appropriate stage in the contract, provision should be made for contract completion or transition planning.

6. Investment in information management

What does good look like?

We expect an information system which records key data on procurement activity/spend.

We expect documentation supporting all procurement activity to be stored electronically and be easily accessible. This might include the original agreement, record of contract progress claims and payments, monitoring and inspection, meeting records, relevant correspondence, records of any variations or claims, producer statements and/or guarantees, and completion certificates.

We expect links between the contract management system and financial management information systems.

Highlights for improvement

|

We found that 77% of TEIs have an information system that enables them to meet core requirements for analysing their procurement spend and managing the procurement process.

Organisations that we assessed to be operating at a lower standard retain information on shared computer drives or spreadsheets.

In most organisations, existing systems provide only core management information. Just two organisations have systems which exceed what we consider to be core requirements for managing procurement. This leaves around 23% of organisations functioning at a level which, in our view, is less than optimal. Several TEIs are reliant on time-consuming manual systems or basic spreadsheet applications. Absence of a contract management information system is a particular feature of small organisations.

A good approach to information management allows organisations to store and analyse information in a way that best suits their needs. This means having access to data which enables analysis, supports planning, and assists the management of the procurement and contract management cycle. When managing contracts, it means having readily available information about the number of contracts in place, their values and end dates, the contracted suppliers, and their performance.

We recognise the financial barriers which may prevent the procurement of systems which are truly fit for purpose, but recommend that data and documentation supporting procurement is accurate and up-to-date. It should be stored electronically, be easily accessible, require minimal manual input, and control unauthorised access. Key data on procurement activity and expenditure is essential. Systems should record all contracts and link to the payment process.

7. Monitoring, review, and reporting

What does good look like?

We expect a comprehensive programme of review, with internal audit reviews of procurement and contract management informed by risk assessment.

We expect to see good evidence of action in response to review findings and recommendations.

We expect to see reporting to and interest from senior management.

Highlights for improvement

|

We found that although most senior management teams are said to be interested and committed to improving procurement and contract management, around half of all TEIs do not adequately review practice in these areas. The frequency of reporting is low in many cases. Commitment to review is a starting point for improvement but must be pursued by involvement in action planning and sharing good practice. We are concerned that some organisations have senior management teams which, according to our information, do not demonstrate the level of commitment to monitoring and review that we expect.

A structured approach to monitoring, review, and reporting of procurement and contract management can provide a valuable contribution towards achieving continuous improvement. Impartial and objective input from those who are not directly involved in the process can also help identify areas for improvement.

Find out more

- auditnz.parliament.nz/assurance-services

- auditnz.parliament.nz/resources/procurement

- auditnz.parliament.nz/resources/contract-management

1: This is based on our review of 22 TEIs audited by Audit New Zealand. These comprise of 13 former institutes of technology and polytechnics (ITPs), six universities, and three wānanga.

2: Sourced from Te Pūkenga annual report for the year ended 31 December 2021.

3: This analysis is limited to 22 tertiary entities audited by Audit New Zealand. These comprise of 13 former ITPs, six universities, and three wānanga.